How Stone Island became the most important brand in menswear

A deep dive on a brand that transcends time and place, + what we can learn from them.

This piece is written in partnership with Stone Island.

The enigma that is Stone Island

I’m from a small, rural town in Florida, where I didn’t have much access to culture growing up. But I‘ve loved clothes for as long as I can remember.

Not in the way people usually mean when they say that. I’m not obsessive about trends or chasing the newest thing. And I’m far from being the smartest in the room when it comes to understanding fabrics, designs, and materials (though I dabble).

No, I’m more interested in how clothing functions as a signal, how it connects people, and how it quietly communicates what you subscribe to or believe in without ever saying a word.

And it wasn’t until I got older that I discovered Stone Island. And like many people my age in the US, my first exposure wasn’t particularly nuanced.

It came through learning about British football culture, hooliganism, and movies like Green Street Hooligans. The more time I spent researching clothing, the more Stone Island kept resurfacing. Not because of the badge, but because of the work behind it.

Because once you look past the surface-level associations, you realize what an enigma Stone Island is.

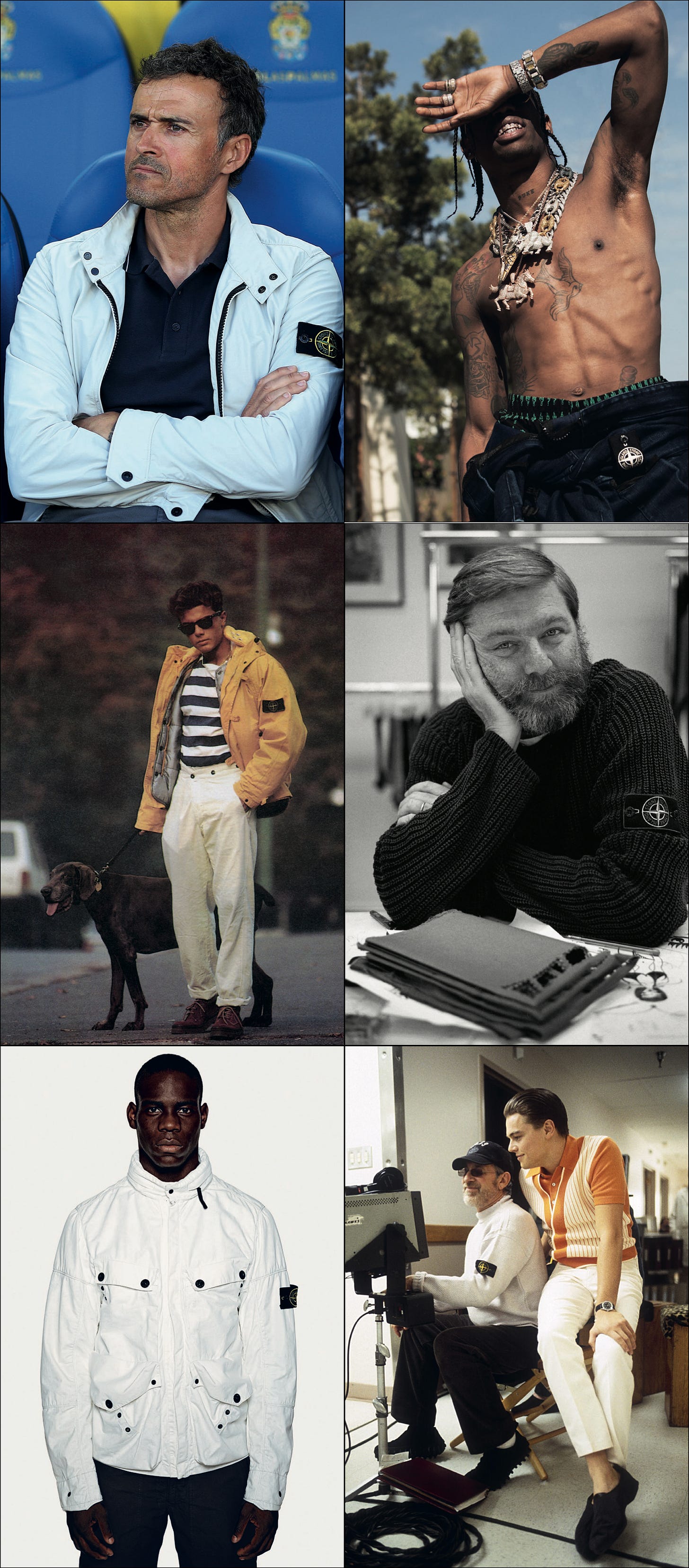

A brand beloved by football fans in Manchester, artists in Detroit, collectors in Tokyo, and guys like me who came to it late, by way of a mediocre Elijah Wood movie.

The surface-level entry points vary wildly, but the people who stick around tend to arrive at the same conclusion:

The magic of Stone Island isn't what it represents… But rather how it's made.

That’s the part of the story that often gets lost, especially in North America.

And it’s the part worth reintroducing.

A brand misunderstood

In Europe, Stone Island is understood differently.

There’s a lived-in knowledge around it. A generational familiarity. People didn’t discover it through pop culture moments or resale spikes; they grew up seeing it worn, beaten up, passed down, argued over.

In Amsterdam, where I reside, I brush shoulders daily with older Dutch men (plumbers, the owner of the local hardware shop, etc.) who often wear the badge.

But in the US, the brand is often reduced to a few things: a logo, a badge, a flex item that floats in and out of cultural relevance depending on who’s wearing it that year.

That reading isn’t entirely wrong, but it’s certainly incomplete.

So, to understand Stone Island, you have to stop reading it as “fashion” and start reading it as research.

The reason Stone Island matters isn’t the same reason a lot of contemporary “luxury” brands matter. It’s not about storytelling first. It’s not about positioning.

It’s about process, and we can trace that philosophy back to its origins.

Massimo Osti and the obsession with process

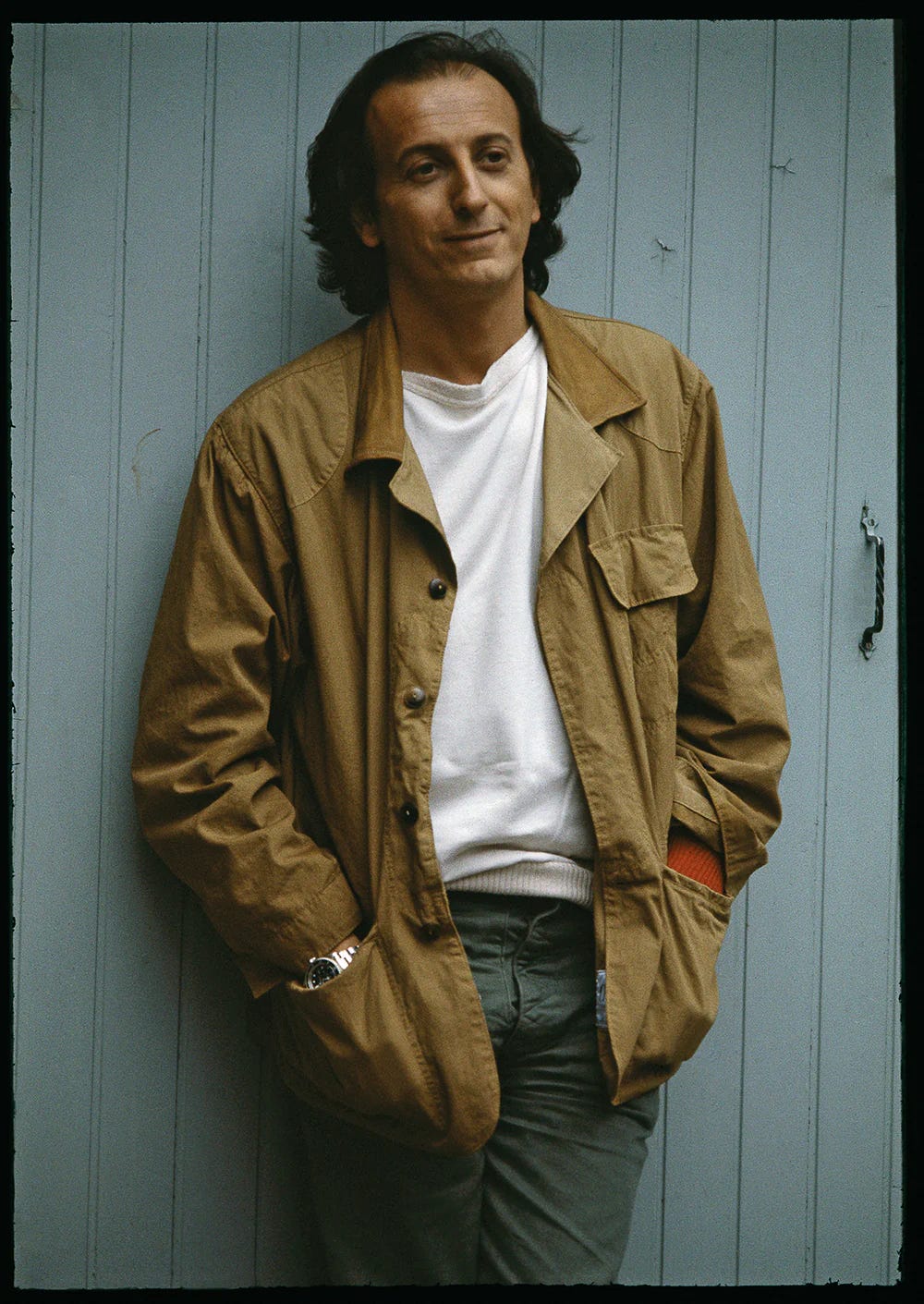

Massimo Osti founded the brand in 1982, and never started Stone Island around a look. He built it around a question: What happens if we treat garments like experiments?

From the beginning, Osti approached clothing the way an engineer or industrial designer might. He was obsessive about materials. About how fabrics reacted to stress, weather, washing, dyeing.

He wasn’t interested in making something precious. He wanted to see what happened when garments were pushed to their limits.

That mentality (of constant testing, iteration, and failure) is still the backbone of Stone Island today.

But let’s back up.

How it spread

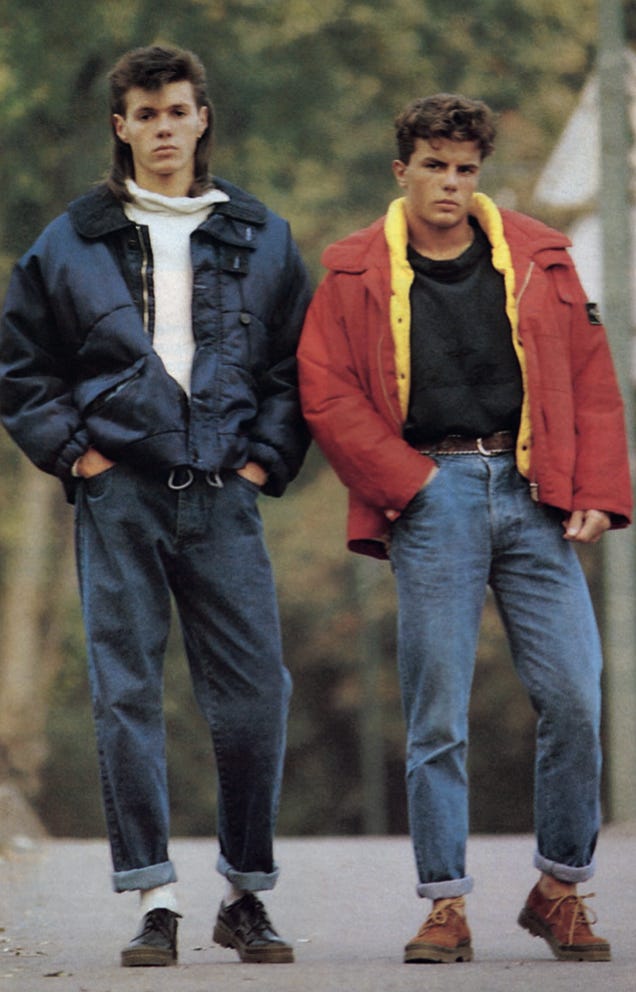

By the mid-1980s, Stone Island had been adopted by the paninari—Italian youth who gathered around Milan’s fast-food joints and treated clothing as a form of identity. They wanted gear that looked expensive but wasn’t delicate. Stone Island fit.

From there, the brand migrated north.

British football fans traveling to European matches brought it home, and by the late ‘80s, Stone Island had become a staple of terrace culture. It wasn’t marketed to these groups. It was discovered by them, passed between cities, traded in pubs, and worn as a badge of taste and toughness.

Through the ‘90s and 2000s, that association deepened. Stone Island became associated with hooliganism, firm culture, and a kind of masculine intensity that overshadowed the product itself. For many people, especially outside Europe, that’s where the story ended.

But the brand kept working. The R&D never paused. While the mythology grew louder, the lab stayed quiet.

The proof is in the pudding product

Garment dyeing is what we’ve known the brand for, but it wasn’t for the vibes. It was a way to recontextualize finished pieces and see how color behaved when applied at the end of the process rather than at the beginning.

And in an industry where so many brands lead with narrative because they don’t have much else to stand on, Stone Island does the opposite. The story comes after the work.

And whether you agree or not, that’s why the brand feels closer, philosophically, to American institutions like Filson, Patagonia, or L.L. Bean than it does to most modern luxury labels.

Innovation isn’t just a tagline for a campaign; it’s the infrastructure.

Avi Gold, founder of Better™ Gift Shop in Toronto, put it plainly when we talked about where Stone Island sits today.

“In true Stone form, it pretty much sits above what everyone else is doing,” he told me. “The reason a lot of us got into the brand was because of their approach to fabrics, techniques, applications. They made timeless garments that withstood the test of time and continue to do so.”

What stood out wasn’t just reverence for the past but also an emphasis on continuity. Stone Island doesn’t romanticize its archive. It reworks it. Old techniques resurface decades later, adjusted, refined, stress-tested again. The same curiosity, applied repeatedly.

“With the rise of accessibility and everyone trying to make product or have a ‘brand,’” Avi continued, “Stone is one of the few brands that continues to stand outside the box and prove themselves through fabrics and their overall approach. It’s like wearable art.”

That idea (proof through product) is increasingly rare. Especially in a market flooded with premium branding and thin substance.

Community as a form of research

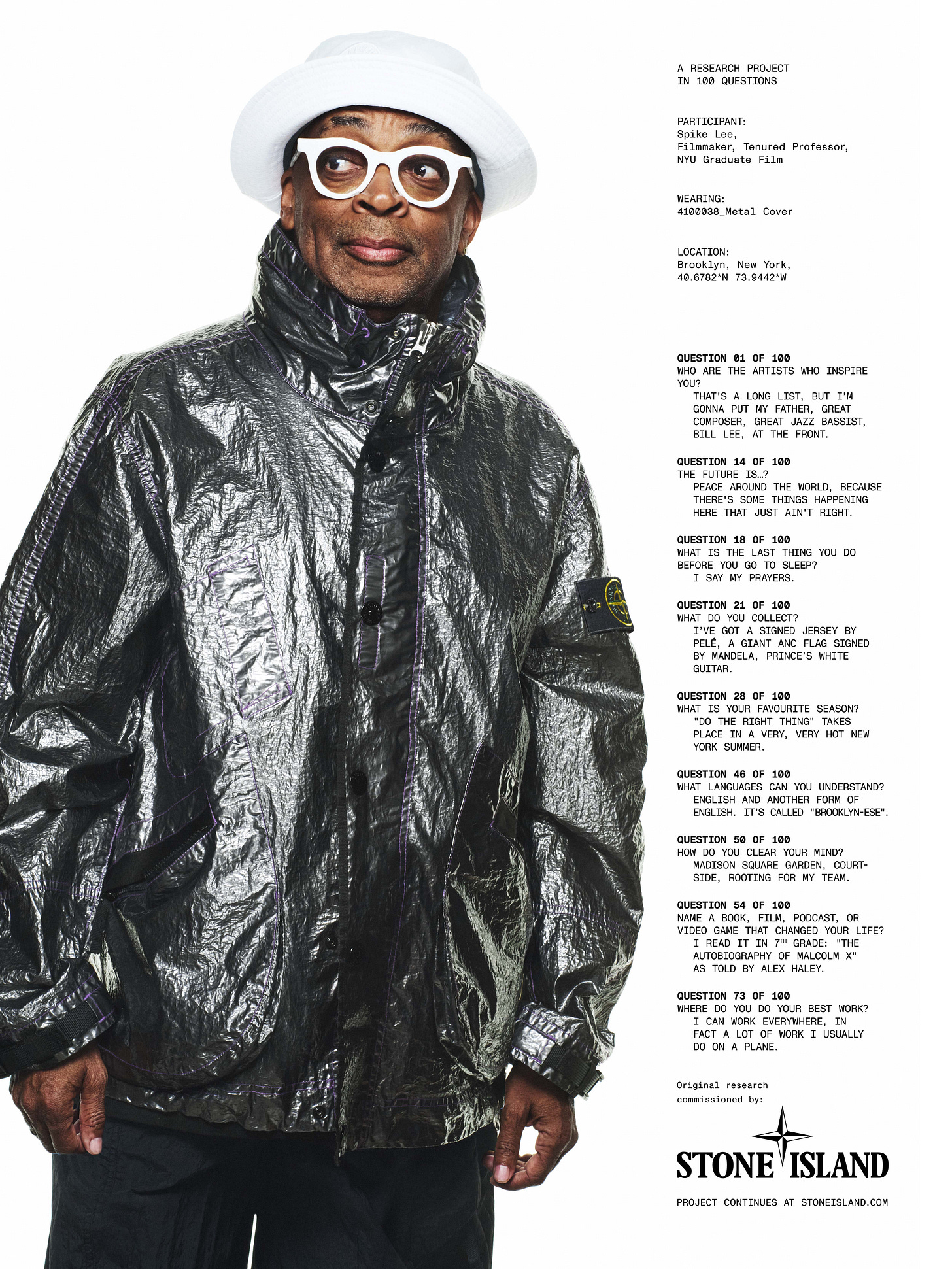

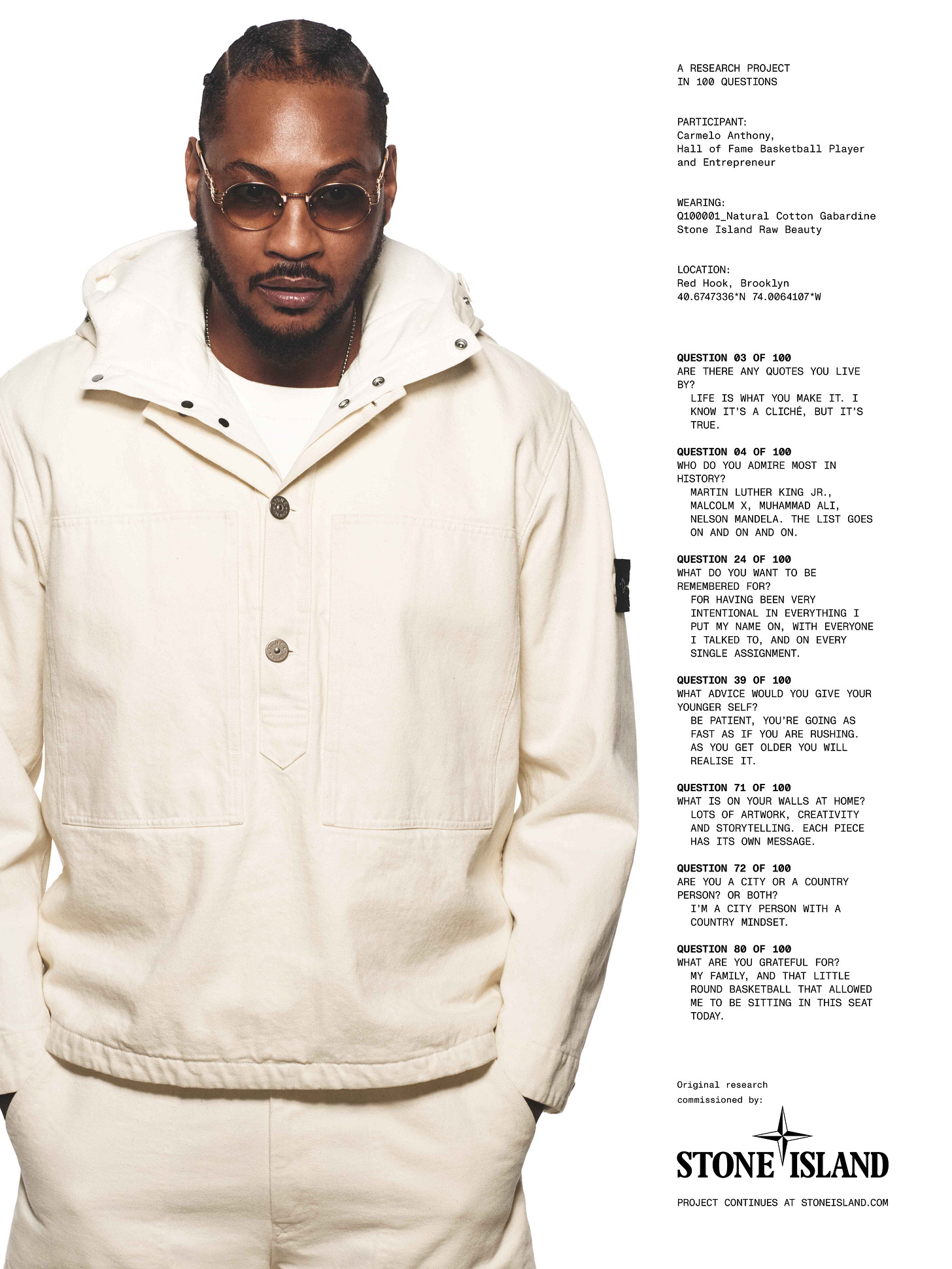

And Stone Island is one of the only brands that treats community not as “marketing,” but as another research surface. The clearest proof is the brand’s own framing: Community as a Form of Research, a campaign concept that puts real devotees at the center rather than hired faces.

The point is not celebrity, it’s evidence. When you photograph people who have lived with the clothes for years, you get a different kind of credibility, and a different kind of information.

What pieces do they keep.

How do they wear them.

What do they return to.

The campaign’s interviews, guided by Hans Ulrich Obrist, turn fandom into field notes, and the short film The Compass Inside makes the same case from another angle: this brand is built through the people who wear it and the people who make it.

That’s what Avi is picking up on.

Stone Island’s community is not a vibe layer added at the end. It’s part of how the brand pressure-tests relevance over time, in the same way it pressure-tests fabrics, dyes, and finishes.

Utility, experimentation, and meaning

Detroit-based Artist Tyrrell Winston approaches materials differently, but the overlap is striking. His work often centers on found objects… things already worn, marked by time, embedded with history.

“When materials wear and change over time, it becomes part of the story,” he told me. “Stone’s fabrics act in a similar way.”

That perspective reframes Stone Island’s obsession with experimentation. It’s not about perfection. It’s about allowing garments to evolve.

“I have no interest in art without experimentation,” Tyrrell said. “That doesn’t mean making things haphazardly. It means not being afraid to go places others haven’t, even if that comes at the cost of not ‘nailing it’ for a while.”

That willingness to be uncomfortable, to fail publicly, and to prioritize learning over immediate payoff is baked into Stone Island’s DNA. And it’s why the brand resists simplification.

Value, in that sense, isn’t fixed. It accrues.

“So much contemporary art could be perceived as nothing if it wasn’t for the story and context,” Tyrrell added. “Stories that stand the test of time become more important than the object, but in turn, they elevate the object.”

Stone Island understands that balance. The product carries the story, not the other way around.

Stone Island rewards your curiosity

Stone Island doesn’t explain itself loudly. It doesn’t flatten its ideas for mass appeal. It rewards curiosity. If you want to understand it, you have to spend time with the product. You have to care how things are made.

That’s why it continues to resonate across such different groups. Football fans. Artists. Designers. Engineers. Collectors. People who don’t dress alike but share a respect for process.

Stone Island isn’t timeless because it looks the same year after year. It’s timeless because it never stops innovating. The brand is a reminder that in a world full of empty promises, the rarest thing is still proof.

And Stone Island, above all else, is proof.

I’m about to put on all my badges today after reading this

Hard